Lana Del Rey, cocaine and the Virgin Mary

How Lana Del Rey's art and music evoke the feminine archetypes of Mexico

“Yo soy la princesa, comprende mis white lines…” moans Lana Del Rey, American singer-songwriter phenomenon, on her hit song “Ultraviolence.” Bilingual queen? But more than a tacky one-liner about being a coke-snorting siren, “Ultraviolence” is just one piece of the tapestry of archetypes Lana creates through her work. Lana Del Rey’s oeuvre has always been rife with cultural references; many of her songs are an ode to iconic female personas in American history, such as Marylin Monroe and Jackie Kennedy, or Biblical ideals, such as angels and sin. But she’s also garnered a reputation as a pseudo-Chicana, using both shallow Hollywood lore and real Latin American mythology to tap into three subconscious Mexican archetypes: la Virgen de Guadalupe, la chigada and la llorona — the pure virgin, the slut and the tragic hysterical woman. Does Lana do these cultural symbols justice or is she too gringa for it to be more than a gross stereotype?

Not-so Virgin of Guadalupe

The story of the Virgin of Guadalupe begins in 1531 when Juan Diego, an Aztec man and convert to Catholicism, received visions upon the hill of Tepeyac near Mexico City to build a church in honour of the Virgin Mary. When Juan Diego went to the city’s bishop, the bishop told Juan Diego to come back with greater evidence of the apparition, not trusting his word as an Indigenous Aztec man. Mary once again visited Juan Diego and instructed him to fill his tilma, or cloak, with flowers. When Juan Diego let down his flower-filled tilma in front of the bishop, it revealed an image of the Virgin Mary imprinted on the fabric. The bishop finally believed him and built the cathedral at the spot of the apparitions. Over the course of several centuries, the cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe grew and was used as a tool by Spanish colonists to de-paganize Mexico’s native people, seen as the Virgin of Guadalupe was revealed to a native person.

Figure 1: Virgen de Guadalupe, 16th century, oil and possibly tempera on maguey cactus cloth and cotton (Basilica of Guadalupe, Mexico City)

Guadalupe represents many things: a symbol of Mexican national identity and culture, Indigeneity, femininity, and of course a Catholic object of devotion. She is described as a mother figure for all Mexicans (Pilar, 2015), in addition to a feminine ideal at once liberating and constricting for both Mexican women (Blake 2008). On one hand, the Virgin of Guadalupe is an important icon of national Mexican identity and a spiritual motivator in the national struggle for independence (Alcalá 2022). The prominence of the Guadalupe also serves, however, the interests of the Catholic patriarchy in maintaining a certain moral order for women. Due Lana Del Rey’s penchant for narratives of womanhood, sexuality and sadness, in addition to her lack of Mexican identity, I argue the latter patriarchal ideal of the Virgin is what her references to Guadalupe most likely signify. A Latin American iteration of the Virgin Mary herself, Guadalupe represents traditional Marian attributes such as purity and piety. The Mexican Catholic church promotes the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe as servient and motherly, which is used to reinforce cultural ideals of female sexual agency and discourage roles for women outside the home, particularly for lower-class Mexican women (Blake 115). This belief is often furthered within Mexican families who immigrate to America, due to a fear that Mexican daughters will adopt the sexually liberal attitudes of American women (ibid).

Figure 2 and 3: Lana del Rey in Tropico (2013) dir. Anthony Mandler (4:19) and in a promotional photograph for the film.

When Lana del Rey clasps her hands and dons her white veil under the glowing blue-green lights in her short film Tropico (Fig. 2 & 3), written by and starring herself to mark the release of her album Ultraviolence, she clearly makes visual reference to the Virgin of Guadalupe (Fig. 1). Her costume is iconographic of the Latino cultural archetype Guadalupe and all that she connotes, such as purity and piety. This connection to Mexican culture is made ever more clear by the scenes in the film that accompany those of the veiled Lana: she is seen lounging with visibly Chicano people and scenes of people wearing the traditional skull makeup of Mexican holiday Dia de los Muertos are interspersed in the film (Fig. 4 & 5).

Figure 4 and 5: Stills from Tropico (2013) dir. Anthony Mandler (10:10 and 10:12).

The Virgin archetype that Lana emulates, however, is not so simple. Evident from her narratives about treacherous love affairs with men (see lyrics below), she tries to portray herself as delicate but is certainly not a pure virgin like the Virgin of Guadalupe. Rather, Lana embodies a virgin-whore dichotomy that parallels the Chingaguadalupe, an archetype first described by Mexican sociologist Roger Bartra (1987). The word is a portmanteau of “Guadalupe” and “chingada”, a Mexican curse word literally meaning “fucked”, but contextually in reference to a woman who has been sexually violated. The Chingaguadalupe represents a binary of expected female behaviour in Latin American Catholic society — virgin purity versus promiscuity — which can be distilled into the dichotomy of Eve and Mary present in the mythological imagination of all Christian societies. Lana plays into this dichotomy in her simultaneous representations of Marian iconography, such as the white veil and the pious woman, and the “chingada”, such as her sensually scorned lyrics and scenes of her dancing for money at a strip club in the Tropico short film.

Additionally, Lana has some lyrics in Spanish, as seen in the titular song of her album Ultraviolence, which largely details an abusive relationship:

Yo soy la princesa [I am the princess]

Comprende [take in] mis white lines

I love you forever (x2)

…

With his ultraviolence

Ultraviolence

I can hear sirens, sirens

He hit me and it felt like a kiss

Throughout both Tropico and “Ultraviolence”, Lana signifies that Latina sexuality and womanhood is plagued with violence. By combining imagery of the Virgin of Guadalupe and Spanish words with lyrics about violence and sexually and emotionally abusive relationships, Lana reinforces the notions of the Chingaguadalupe trope, a woman who is both sexually violated and trapped by rigid ideas of feminine purity.

The weeping woman: La Llorona

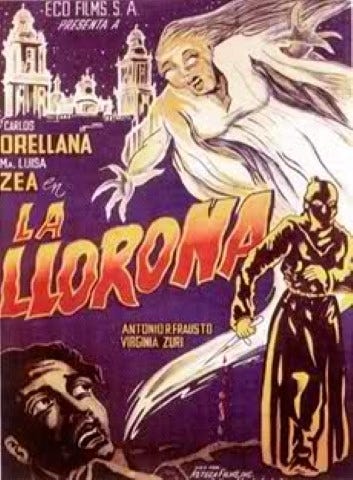

The Mexican legend of la Llorona (the weeping woman) changes and morphs depending on its geographical and historical context, but its tragic storyline remains the same. It is the story of a woman whose lover betrays and leaves her after she has their child. The woman then takes the life of their child before committing suicide in a fit of sadness and rage. The woman is typically portrayed as an Indigenous Mexican woman in popular folklore and media, while her lover is a Spanish Conquistador. Although mainly an oral tradition, records of the story of la Llorona exist from the late 19th century. It first appears in film in the seminal 1930 Mexican horror movie La Llorona, in which the Llorona character is a Tlaxcaltecan princess and has a son with a powerful Spanish man, who eventually betrays her and leaves her for a woman of his race and class. La Llorona survives as a ghost, wandering and wailing for her murdered child and lost lover.

A llorón (fem. llorona), is a person who cries excessively (Diccionario Real Academia Española). Lana Del Rey is a perfect llorona: she is famous for the luxuriant sadness prominent in her lyrics and sound. Her voice is highly distinctive for its drawn-out, low and weeping quality. In her song “Pretty When I Cry,” Lana Del Rey laments about a lover that leaves her and treats her poorly just like the la Llorona and her Conquistador.

I'll wait for you, babe, that's all I do, babe

Don't come through, babe, you never do

Because I'm pretty when I cry

Lana’s devotion and self-sacrificial sadness over a man who continues to leave her parallels la Llorona’s reckless and love-blind behavior. La Llorona, the horror film, portrayed la Llorona as overflowing with emotion, intensity and madness. Lana’s weeping persona builds upon the cultural myth of la Llorona and both contribute to the Western notion that excess emotion and insanity are tropes of feminine behavior.

The feminine-coded madness that both Lana and La Llorona embody is furthered in the songs from Lana’s 2015 album Honeymoon. The album particularly features the songstress singing in a high-pitched, haunting tone. In “24”, Lana weeps about a man who has left and betrayed her.

[Verse 1]

There's only 24 hours in a day

And half as many ways for you to lie to me, my little love

There's only 24 hours in a day

And half of those, you lay awake

With thoughts of murder and carnage

“The Blackest Day”, from the same album, contains similar themes:

Ever since my baby went away

It’s been the blackest day

…

Because I'm going deeper and deeper

Harder and harder

Getting darker and darker

Looking for love

In all the wrong places

Oh, my God

Like La Llorona, Lana looked for love in the wrong places and ended up sinking into a dark depression.

Lana Del Rey has come under particular scrutiny throughout her career for “romanticizing domestic abuse” and toxic relationships, but she argues she only gives an honest portrayal of her own experiences. In an interview with the BBC, Lana stated that “if [she] even expressed a note of sadness in [her] first two records, [she] was deemed literally hysterical as though it was literally the 1920s". Evidently, Lana did not intend for her music to be interpreted as symbolic of the female hysteria trope such as la Llorona, but her critical reception demonstrates how her music evokes the cultural psyche regardless. Her aesthetics only serve to further the llorona trope: she is often photographed wearing flowy white dresses (Fig. 7 & 8) that resemble the flowy white gowns of a ghost — a haunting woman whose soul is unsettled (Fig. 6). Although inadvertently, Lana became a modern llorona.

Figure 6: La Llorona (1933) posters (IMDb).

Figure 7 and 8: Lana Del Rey photographed performing (REUTERS/Dominic Favre/Pool, 2012) and in a photoshoot for her album Honeymoon (2015).

The triad of tropes

The chingada, la Llorona and the Virgin of Guadalupe have been argued by many scholars to form a triad of female archetypes in the Mexican cultural imagination. Melero (2015) argues that these three make up the principal “Mexican constructs of femininity” that determine ideas around motherhood and women’s societal expectations. These three tropes are all contrasted against each other and may surface in Mexico’s cultural and political discourse at any time; they are invoked, for example, to criticize and insult the wives of corrupt politicians that the people find treacherous or complicit in harming the nation. La chingada and la Llorona are demonized whereas the Virgin of Guadalupe is revered.

Although the veiled woman, the promiscuous woman and the overly-emotional woman are universal tropes in the Western imagination, by combining them with the Spanish language and symbols of Latino culture, Lana makes their perception as the Guadalupe, the chingada and la llorona unmistakeable. Between her overt depiction of the Chingaguadalupe trope and her la Llorona undertones, Lana has created a rich narrative of female pain that carries ties to Latin American popular mythology.

Lana Del Rey and Cultural Insensitivity

Lana Del Rey is the stage name of Elizabeth Grant, a white American who grew up in a middle-class family (Rolling Stone, 2014). Despite this, Lana stars in what seems to be an exploration of the stereotypical Latina-American experience in Tropico. In the short film, Lana is surrounded by people of visible Indigenous Latino descent who engage in gang activity and snort cocaine. Her lyrics — “Comprende mis white lines / You’re my drug dealer / I love you forever” — indicate a tie between Latin America and drugs and crime. Lana has a persistent fascination with cocaine, a drug that hails from South of the United States border: in 2012, she released a song titled “Yayo”, Spanish slang for cocaine. Not to mention, her name itself is Spanish - Del Rey translates to “of the King.”

Lana del Rey’s heavy inspiration from tropes of the plight of Latin American women offers space for interesting interpretation, but ultimately lacks nuance due to her position as a non-Latina. She undeniably mythologizes and renders cinematic the sexist and drug-based violence and ideas that trouble some Latino communities. It may be argued that Lana could be commenting on the violence inherent to the sexist tropes and cultural myths that are at the root of Latina pain in a way that is stylized but not exploitative. However, I argue that because Lana is a white woman who places herself as protagonist in Latina experiences and tropes, she conveys a degree of naive insensitivity; this is evidently a young woman shaped by Hollywood, for better or for worse. She has not experienced life as a Mexican woman, and this is made evident by her choice to only represent Mexican culture in the context of drug use, gang violence and toxic sexual situations. The more universal Western tropes that lie at the foundation of the Mexican mythological triad, such as the Virgin Mary, female hysteria and the “whore”, are treated compellingly by Lana. Many of her lyrics convey the painful vulnerability of womanhood and sexuality. By tying them into a version Latino culture that is portrayed as vice-ridden, however, she perpetuates stereotypes rather than deconstructs them.

In conclusion, despite her non-Latina origins, Lana messily traverses the landscape of Chicana culture with both artistic flair and severe naiveté. Regardless of how you read into these politics, there’s no denying: that’s why they call her Lanita.

Bibliography

Alcalá, Rita Cano. “La Malinche, La Virgen de Guadalupe, and La Llorona: The Recuperation of Divine Supernatural Powers in Late 20th-Century Chicana Literature.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature. Oxford University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.355.

Blake, Debra J. 2008. Chicana Sexuality and Gender Cultural Refiguring in Literature, Oral History, and Art. Durham: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822381228.

Hiatt, Brian. July 31, 2014. “Lana Del Rey: Vamp of Constant Sorrow.” Rolling Stone Magazine. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/lana-del-rey-vamp-of-constant-sorrow-74230/7/

Melero, Pilar. 2015. Mythological Constructs of Mexican Femininity. 1st ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137502957.

Savage, Mark. May 21 2020. “Lana Del Rey: I’m not glamourising abuse.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-52753775

that’s why they call her lanita 😌

Virgin, mother and whore are archetypes that predate european colonisation of the Americas.